Who I was before and after:

In order to contextualize this experience, part of the reality is that I am twenty-one years old, female, Korean-American, and have spent the last seventeen years of my life as a student at various institutions. I mention this because there was something inescapably personal about participating in this GISP.

Before undergoing this course, I predominantly identified as a RISD student for a combination of reasons. My first year in college was primarily spent at RISD so, naturally, I assimilated to RISD values, culture, and social groups. Disconnected from Brown, I developed a bias that made it difficult to transition into my second year. At Brown, not only did I feel detached and invisible, I became hyper-sensitive to academia and its criteria of judgment. Moreover, I had internalized a stigma around “intellectualizing” or “overthinking” art, which further gave me reason to distance myself from Brown. My initial alliance with RISD alongside my discomfort at Brown, gradually resulted in the dismissal of my Brown education. When confronted with the question of integration and interdisciplinarity, a question I felt was implicit in this program, I concluded that my studies in geology will remain subservient to my sculpture practice. This decision felt unsatisfactory, and by the end of my sophomore year I felt utterly lost, confused, and strangely incapable of trusting myself. I would like to note that I do not mean to criticize the structure of the program, but simply to describe my previous thoughts and experiences, all of which have been challenged throughout this course. In other words, much of what I felt was due to me, not the program.

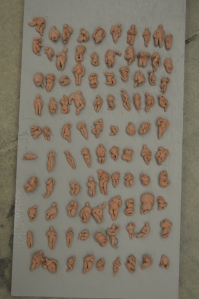

By the end of this Wintersession, I got a taste of what it feels like to deconstruct perceived external pressures and not subscribe to the definitions of either institutions but instead to myself. When I was authentic with my feelings and process, who I became was someone more amorphous, someone irreducible to labels like “geologist” and/or “sculptor”. Actually, I am neither a “geologist” nor a “sculptor”, for that matter, but just a student only beginning to investigate these fields and herself. These insights were liberating and I no longer felt threatened by my education, but empowered. In general, I became more comfortable during times of ambiguity and states of imbalance, thus more confident and open to my future years in this program.